*

How to hand-raise & Author Bio

*

How do you begin a poem?

First thing in the morning, I read other people’s poetry, aloud. I read everything I can, from contemporary to ancient, in Scots, in English, in translation …and yes aloud. Someone said that for every poem you write, you read forty. I think that’s about right. Not all at once, but yes…forty to feed one. Then, I walk (and in warmer days swim). There’s something about being outside, for me. Words begin to clutter and cluster, knock into one another in my head. The poem starts there.

If I have a particular subject to tackle, I often borrow the Anglo-Saxons’ idea, and write a riddle. That helps me find a way under the skin of a metaphor and understand my subject better. So sometimes that gives me two poems for one!

*

When did you start writing poetry, and when did you start reviewing it?

I wrote poetry when I was at school, but after a gap, in later years when I found myself writing more, it was predominantly short stories. I started an M.litt at Dundee University, and then began to write more and more poems. I am indebted to the huge support and encouragement I received there, both from the staff (Kirsty Gunn, the much-missed Jim Stewart and from Gail Low), and the creative community which continues to thrive there. Kirsty has a way of making terse, written comments, which say a huge amount in very few words. “Your short stories want to be poems.” I found that they did.

Gail set up DURA nearly five years ago, and asked me to review a poetry collection. Then I seemed to be reviewing and editing other reviews …five years and still going on. I’m not quite sure how that happened!

*

Do you find that reviewer voice influences the way you write and edit your own poetry?

One of the wonderful things that reviewing has done for me is that I have read poetry I’d not otherwise necessarily have chosen in a library or shop. If a collection is published it has already gone on a considerable journey to reach a reader. Not being appealing at first glance is not enough, and you have to read closely, respect and understand what makes that work stand, whether it is to your taste or not. I think that opening yourself to possibilities, not perhaps always of your choosing, is a terrific opportunity for any poet.

So, that ever-widening reading does echo in my head as I write, and edit my own lines. Then I hear Jim Stewart’s pithy thoughts. Dundee’s beloved Jim died in June, and though I miss him terribly, and want to ask more, much more, his words and advice continue to underscore every poem I write. I also hear Helena Nelson – her reading window is a hugely generous service to poets everywhere, and I have no idea how she manages it. Then there was a poetry surgery with the equally wonderful John Glenday. I ran home from that not with the six poems he had advised me on, but desperate to apply his advice to everything I was writing. Those three voices continue in my head, but certainly no less importantly, I have so many dear friends who gathered through the M.litt and who continue to crit, support and advise. Lindsay Macgregor and Nikki Robson stand out. Jo Bell’s 52 was an amazing experience, and some of the continuing online support which had its roots there (Ruth Aylett, Catherine Ayres, Seth Crook, David Callin and more) has greatly nurtured and inspired me.

*

What’s your favourite poem you’ve ever encountered, and when did you encounter it?

I honestly can’t single out one poem! I could mention almost anything by Heaney, MacCaig, Donne …too many! It is such a privilege to read Scots translations of classical Chinese poets. Where could I start? However, I suppose I have a very dear place for Les Murray’s “It allows a Portrait in Line Scan at Fifteen”. When I first read it aloud, but in the quiet of my own home, I jumped up and down, punched air. YES!! I saw how the great Australian understands his son’s autism, and untangles it from his son’s unique and precious personality. I was in tears, and I am again,every time I read it. Everyone with personal and professional experience of autism should be given that poem. Sometimes when I need to pull the thread of an experience I have had, in order to be able to write about my own son, I turn to Les Murray’s extraordinary pattern.

I’d also like to mention Jamaican poet Tanya Shirley’s “Edward Baugh, When I Die”, because it’s the best funeral plan I have ever read. I suspect the Co-op will struggle to manage it for me, but it will be perfect. I’m tempted to mention her countryman Kei Miller’s work, but I’d really never stop answering your question!

*

The Handfast poetry duets is a lovely idea. Was the anthology your first collaboration, and did you find it challenging/rewarding/both?

Working with Ruth on Handfast was a huge privilege. I have worked collaboratively with visual artists, but never with another poet. I would certainly recommend it. Again, that imposed certain very constructive and positive editorial disciplines. I expected that we would have more professional and respectful disagreements than in practice we did. Although we are very different poets we worked well together, and it was a great to see our work interact. Certainly for me, it was an entirely positive experience which helped me develop as a poet.

*

How did you jump from Silversmithing to an M. Litt?

Perhaps it wasn’t so much a jump as a long swim! My parents and English teacher would have liked me to go to University at seventeen, but instead I headed to Glasgow School of Art. I have no regrets about that, and like anyone who ever studied at GSA, those years are very much part of me. Words have always mattered hugely though, and although I was tremendously happy teaching Art in various situations, increasingly I felt my creative direction was in language. I started odd classes, and asked about doing something more. I was shocked when Jim Stewart suggested an M.litt. Even as I started the course, I was sure he and Kirsty had made a mistake. I was heading for fifty, and not being sensible. Jim Stewart’s confidence in me changed my life.

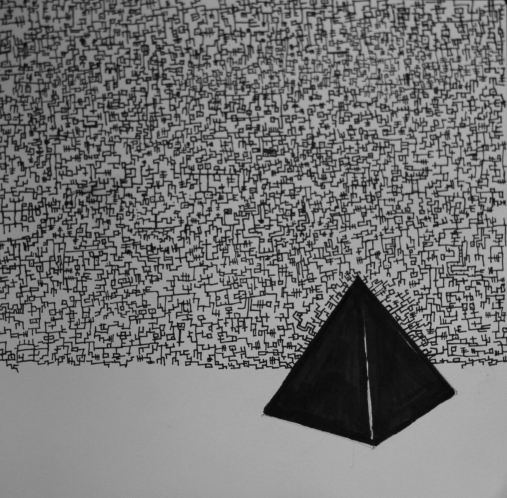

Yet, there’s a connection, isn’t there? What might draw someone to the tiny, intricate and beautiful concerns of making a silver box might equally make someone write a poem. I think they’re not so very different. Though I’m no longer a smith, I continue to work many of my poems out into mixed media visual works. I feel very lucky to be able to try to understand what is an interesting, and not always easy life (whose is?) creatively.